About The Program

Don’t Pack A Pest helps protect U.S. agriculture from harmful invasive species. When traveling internationally, seemingly innocent items like fruits, vegetables, or handcrafted goods can accidentally bring dangerous pests into the country. With millions of travelers passing through Texas’s airports, seaports, and border crossings each year, we need everyone’s help to track agricultural items by declaring them to port inspectors.

Spreading invasive pests can devastate our resources. And even if it’s not intentional, it only takes one person to cause widespread damage. Luckily it only takes one simple declaration to help prevent big problems. So when in doubt, point it out. Declare your agricultural items when you travel.

What Should I Declare?

Show More

Plants, Seeds, and Soil

May require a phytosanitary certificate or permit.

Natural Medicines

Dietary and nutritional supplements containing animal ingredients like gelatin or bone marrow.

Dairy products

Except hard cheese like cheddar and parmesan.

Meats

Meat and poultry may be restricted based on country of origin.

Fruits and vegetables

Including fresh, frozen and most dried products.

Wood

Wood products and handcrafts.

Raw Eggs

Including products that contain raw eggs.

Dried Soup Mixes

Including bouillon that contain meat or poultry.

Travel Tips

- Before you shop for souvenirs, find out what’s okay to bring back.

- Remember, many items are available in the U.S., so there’s no need to bring them with you.

- Don’t pack any meat products or fresh fruits, vegetables or plants without first checking to see what’s allowed.

- If you visit agricultural areas, be sure to clean your shoes to get rid of any unwanted hitchhikers.

Did

You

Know?

Texas currently has 29 official entry ports. That’s more than any other state!

View Ports

How to Declare

Self Service

Find a self-service kiosk when you get off the plane.

Mobile App

Use Form 6059B on your Mobile Passport App.

Download the Declaration Form

The Customs and Border Patrol Declaration Form 6059B helps us with basic information about who you are and what you’re bringing with you into the United States.

Ask an Agent

Tell one of our U.S. Customs and Border Protection officials if you’re traveling with any food or agricultural products in any of your bags.

When in Doubt, Call it out

The U.S. Customs and Border Protection officials can check your items to be sure they’re pest and disease free.

Top 10 Most Unwanted List

This lineup of pests are the biggest threats to our agriculture

Show More

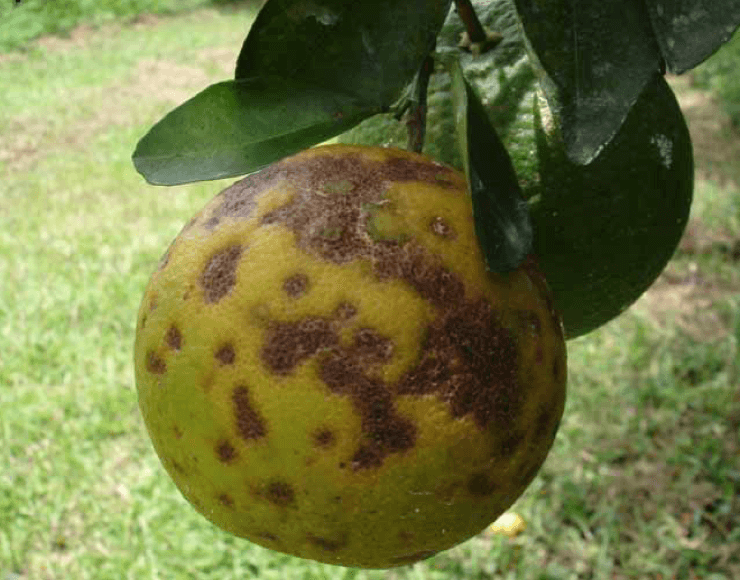

Citrus Leprosis

Citrus Leprosis (CiLV) is an economically important viral disease that can damage citrus crops. Symptoms include small, brown spots— commonly referred to as nail-head rust—that appear on fruit, leaves, and twigs of affected trees. This emerging disease is widely distributed in South and Central America, from Argentina to Mexico but not yet present in the U.S. It is transmitted by Brevipalpus mites. Mites can become airborne and can be carried with citrus fruits, plant parts, and with passenger luggage or cargo from the infested citrus growing areas.

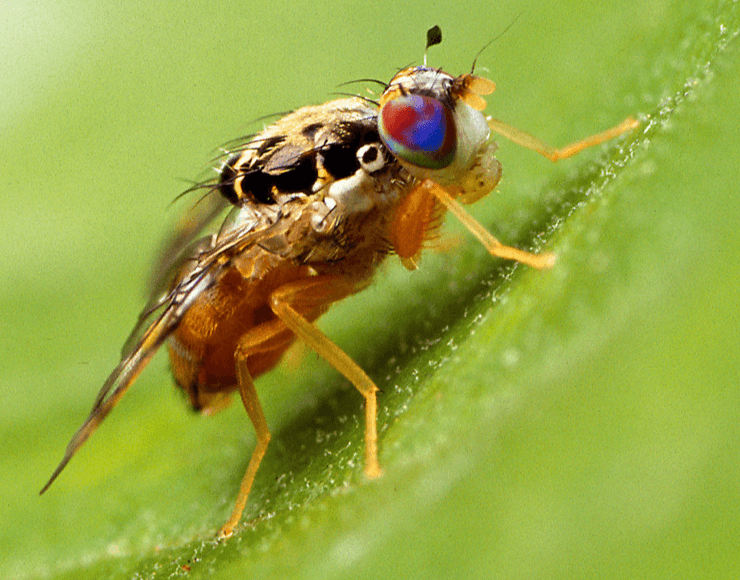

Mexican Fruit Fly

The Mexican Fruit Fly (Anastrepha ludens) is a serious pest to various fruits, particularly citrus and mango. The Mexican Fruit Fly was first found in Central Mexico in 1863, and by the early 1950s flies were found along the California-Mexico border. Many commercially grown crops, including avocado, grapefruit, orange, peach, and pear would be threatened if the Mexican Fruit Fly becomes established. The sources of threat are fresh produce, fruit and vegetables brought into the U.S. or across state borders without inspection.

Each year, the pest enters the Lower Rio Grande Valley’s 27,000 acres of commercial citrus crops from south of the border and attacks more than 40 different kinds of fruits. Damage occurs when the female fly lays eggs in the fruit, which then hatch into larvae, making the fruit unmarketable.

Currently, the Texas Department of Agriculture maintains an active quarantine for the Mexican Fruit Fly and is engaged in its eradication with our USDA partners.

Mediterrranean Fruit Fly

The Mediterranean Fruit Fly (Ceratitis capitata or Medfly) is considered the most important agricultural pest in the world. The Medfly has spread throughout the Mediterranean region, southern Europe, the Middle East, western Australia, South and Central America and Hawaii. It has been recorded infesting a wide range of commercial and garden fruits, nuts and vegetables, including apple, avocado, bell pepper, citrus, melon, peach, plum, and tomato.

Emerald Ash Borer

The Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis or EAB) is responsible for the destruction of tens of millions of ash trees in 30 U.S. States. Native to Asia, it likely arrived in the United States hidden in wood packing materials. The first U.S. identification of Emerald Ash Borer was in southeastern Michigan in 2002. The sources of threat are firewood, ash wood products, ash wood packing material, infested nursery ash plants, ash wood debris and trimmings, including chips. These materials can spread the infestation even if no beetles are visible.

Texas is particularly at risk because species of ash (Fraxinus spp.), including many native to Texas, are vulnerable. In many Texas cities, ash is an important ornamental tree in landscapes and along streets.

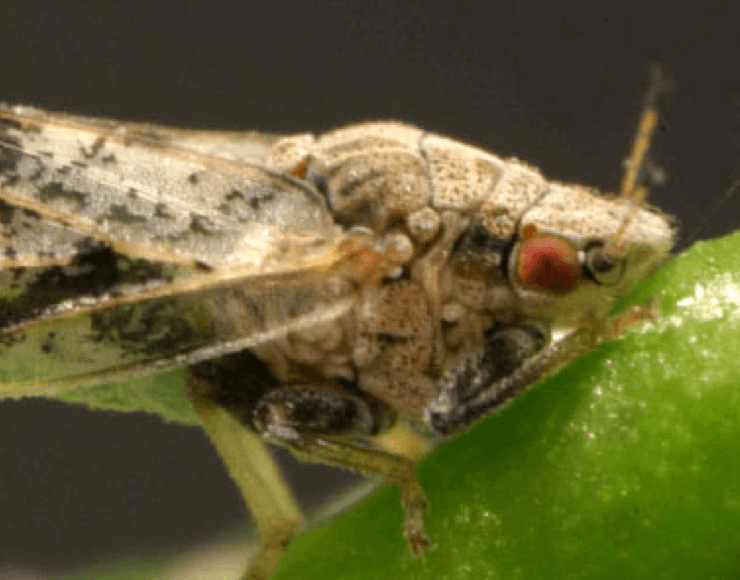

Asian Citrus Psyllid (HLB or Citrus Greening)

The Asian Citrus Psyllid (Diaphorina citri kuwayama or ACP) causes serious damage to citrus plants and citrus plant relatives. Burned tips and twisted leaves result from an infestation on new growth. Psyllids are also carriers of the bacterium that causes Huanglongbing (HLB) disease, also known as citrus greening disease, spreading the disease to healthy citrus plants. Citrus greening is one of the most serious citrus plant diseases in the world. Once a tree is infected, there is no cure.

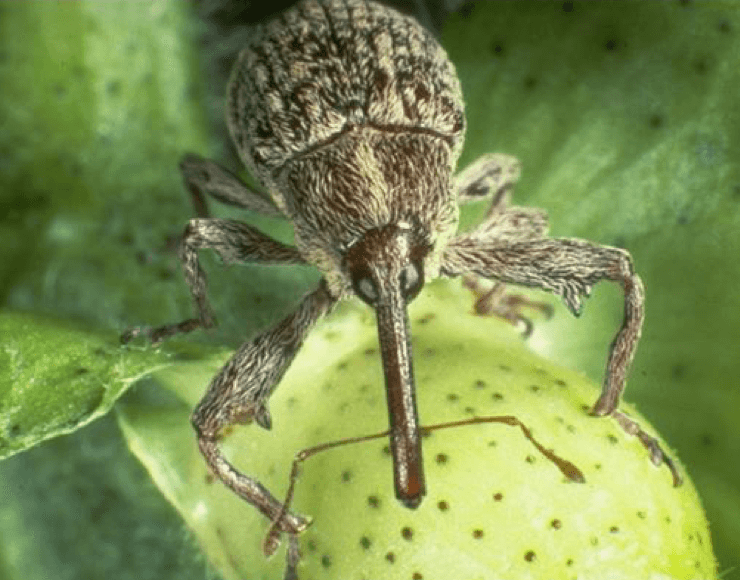

Cotton Boll Weevil

The Cotton Boll Weevil (Anthonomus grandis) is a beetle native to Mexico and Central America. It was first introduced into the United States near Brownsville, Texas, in about 1892. By 1922, the pest had spread into cotton growing areas of the United States from the eastern two-thirds of Texas and Oklahoma to the Atlantic Ocean. Boll weevils feed on and reproduce in cotton. Both the feeding and reproduction processes damage bolls on the cotton plant ultimately reducing quality and the amount of cotton lint available for harvest. The Boll Weevil has cost the cotton industry $23 billion in economic losses since it moved into the United States from Mexico.

As the number one cotton producer in the United States, Texas is active in the fight against this invasive pest. The Texas Department of Agriculture (TDA), in collaboration with the Texas Boll Weevil Eradication Foundation (TBWEF) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), assists cotton farmers in increasing efficiencies, eliminating duplication of efforts and streamlining the process of cotton stalk destruction — all of which work to eradicate Boll Weevils from Texas’ cotton crop. Prior to the eradication efforts, Boll Weevils caused an estimated $200 million in losses per year to Texas farmers.

Parts of Texas bordering with Mexico continue to battle the Boll Weevil, where the effects of border violence and funding hardships for Mexico’s eradication programs create challenges in the much-needed progress towards eradication. The continued collaborative efforts of industry leaders, farmers, TBWEF, USDA and TDA are key to future successes in these areas.

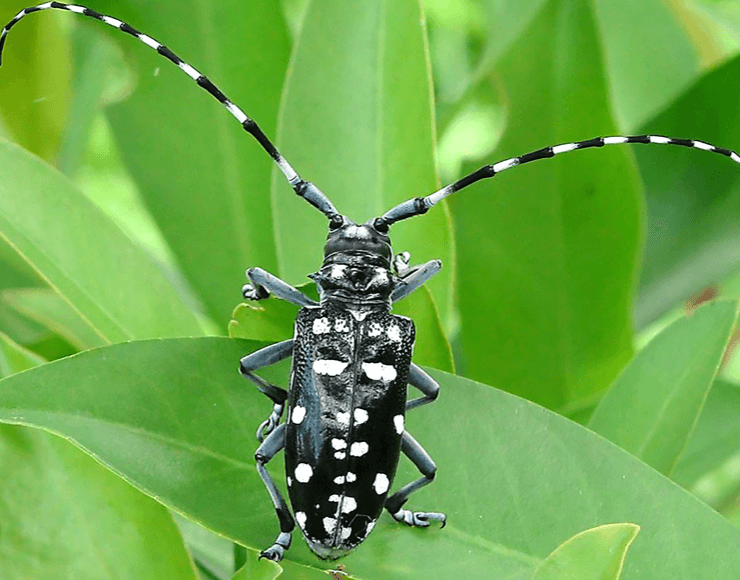

Asian Long Horned Beetle

The Asian Long-horned Beetle (Anoplophora glabripennis, or ALB) is a threat to American hardwood trees. With no current cure, early identification and eradication are critical to its control. It threatens recreation and forest resources valued at billions of dollars. The ALB has the potential to cause more damage than Dutch elm disease, chestnut blight, and gypsy moths combined, destroying millions of acres of America's treasured hardwoods, including national forests and backyard trees. The sources of threat are eggs, larvae, and hitchhiking adults in firewood, solid wood packing material, wood debris and trimmings, branches, logs, stumps, and lumber even if no beetles are visible.

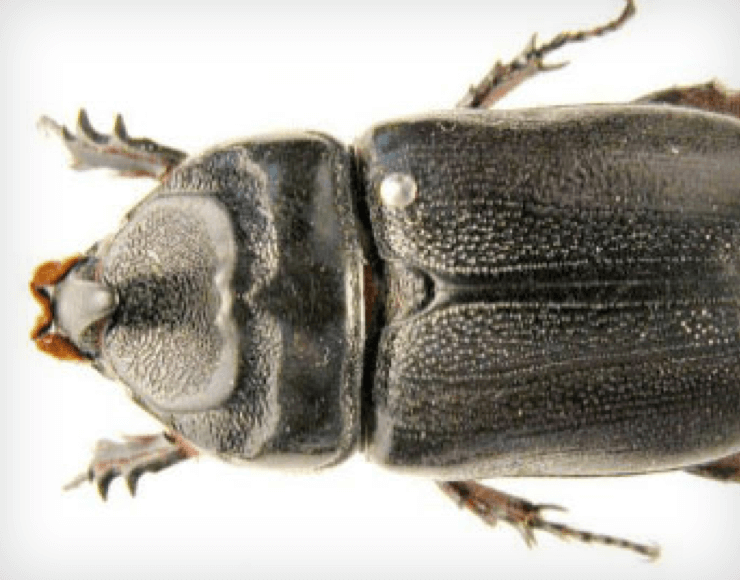

Khapra Beetle

The Khapra Beetle (Trogoderma granarium) is one of the world’s most destructive pests of stored grain products and seeds. Its feeding damage often spoils 30-27 percent of the product. Established infestations are difficult to control because the beetle can survive without food for long periods, requires little moisture, hides in tiny cracks and crevices, and is relatively resistant to many insecticides and fumigants.

Asian Gypsy Moth

Asian Gypsy Moths (AGM, Lymantria dispar asiatica, Lymantria dispar japonica, Lymantria albescens, Lymantria umbrosa, and Lymantria postalba) are exotic pests not known to occur in the United States. If they would become established here, they could cause serious, widespread damage to our country’s landscape and natural resources. Each female moth can lay hundreds of eggs that, in turn, yield hundreds of voracious caterpillars that may feed on more than 500 tree and shrub species. Large AGM infestations can completely defoliate trees. Repeated defoliation can lead to the death of large sections of forests, orchards, and landscaping. AGM females fly long distances can quickly spread throughout the United States.

Coconut Rhinoceros Beetle

The Coconut Rhinoceros Beetle (Oryctes rhinoceros) was first detected in Hawaii in December 2013. This invasive pest is native to southeast Asia. It attacks coconut palms by boring into the crowns or tops of the tree where it damages growing tissue and feeds on tree sap. The damage can significantly reduce coconut production and kill the tree. The beetle is also known to feed on economically important commercial crops such as bananas, sugarcane, papayas, sisal, pineapples, and date palms. The sources of threat are movement of infested compost, mulch, and green waste, bringing infested plants into the United States in passenger baggage, and beetle hitchhiking in international cargo.

Bad Pests Runners-up

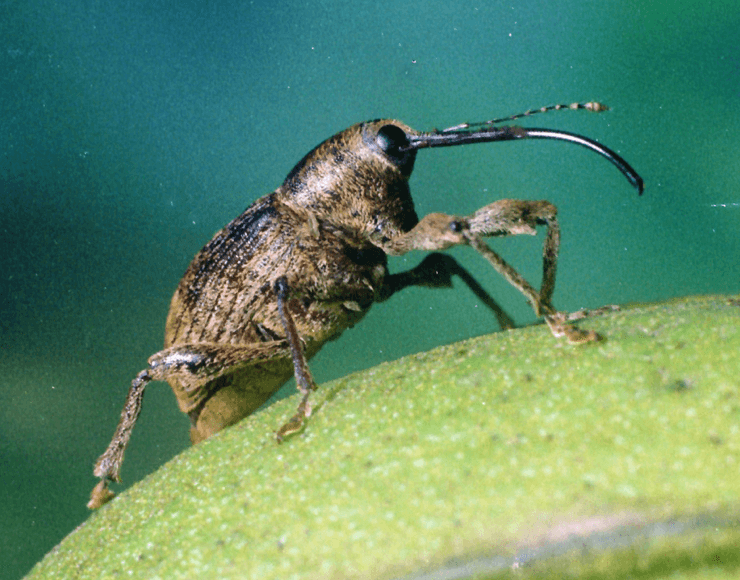

Pecan Weevil

The Pecan Weevil (Curculio caryae) is a dangerous nut pest of the pecan found throughout the southern United States and portions of Texas. The adult is a brownish weevil, about 3/8 inch long. The female’s snout is as long as its body; while the male’s snout is somewhat shorter. The larvae are cream colored grubs with reddish heads. When fully grown, larvae reach a length of 3/5 inch. Pecan weevil infestations reduce nut yield at two points in the growing season. In the summer, adult weevils puncture and feed on immature nuts, causing the nuts to abort. Later in the growing season, mated females chew a hole in the pecan shell and deposit eggs inside. Larvae consume the developing kernel, rendering it unfit for human consumption. Sources of infestation include moving untreated pecan nuts in the baggage or in cargo from the infested area.

Old World Bollworm

The Old World Bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera) is known to attack more than 180 plant species and can cause damage to crops such as corn, cotton, small grains, soybeans, peppers, tomatoes, and beans. Damage occurs when the larvae feed on the leaves of host plants and bore into the flowers and fruit and feed within the plant. The threat is from moving, mailing or bringing infested fruits, vegetables, or plants into the United States in passenger baggage and moths or larvae hitchhiking in international cargo.

Meet Linus

have you ever seen this furry don’t pack a pest mascot?

Meet Linus. He’s an official CBP detector dog who served the Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport until his retirement in 2015. Linus and other detector dogs like him are responsible for sniffing out agricultural items that could be carrying invasive pests or diseases at our ports of entry.

Declare your agricultural items when you travel. It’s a simple way to make a dog’s day.

QUESTIONS? ASK LINUS.

Who needs to fill out a form?

Both visitors and U.S.

citizens should fill out entry forms.

Does everyone in my family need to fill out a form?

Immediate

family members traveling together only need to fill out one form for your travel party.

What do I declare?

Let us know if you have any fruits,

vegetables, meats, plants, seeds, soil, animals, or plant or animal products.

That includes everything in your checked bags, carry-ons and your vehicle.

Will you automatically take my items?

Our CBP agriculture

specialists will simply examine your declared items to determine if they meet

the U.S. entry requirements.

Why do you need to know if I visited a farm?

If you’ve been

around foreign agriculture or livestock, your shoes or luggage may carry traces

of soil that could contain harmful animal diseases like Hand, Foot and Mouth

Disease, and we don’t want that to spread.

Still have questions?

Contact Us

Our History

Everything’s bigger in Texas, including its borders! With over 1,200 miles of Mexican border, dozens of bustling airports, and busy seaports welcoming millions of cruise passengers each year, Texas is like a giant welcome mat for visitors – and unwanted pests. That’s why Texas joined the Don’t Pack a Pest fight against invasive species in 2018. We know that every suitcase that crosses our borders could be carrying an uninvited guest that threatens our diverse ecosystems and agricultural livelihoods.